This article will discuss the Individual Graduation Committee Process for students who have not passed all five of the EOC exit exams as they approach graduation. This articles does not address the graduation options for Special Education students. It does include any student covered by a 504 plan. The IGC process allows a student to graduate by committee decision if they have failed to comply with the EOC requirements “for not more than two courses.” So let’s start at the beginning and walk through it.

The Texas Education Code requires passage of five End of Course assessments to receive a diploma from a public high school. (CITE). Those five courses are English I, English II, Biology, Algebra I and US History. Three of those are usually taken in ninth grade, one in tenth grade and one in eleventh grade. A student who does not pass the assessment has another opportunity in the summer and then three opportunities in each following year to try to pass. So a parent who permitted their kid to stay on this merry go round could potentially have their kid take 46 EOC assessments while chasing that paper.

Fortunately, there are alternatives. Many parents choose to have their kids attempt substitute assessments. But usually when a parent comes here looking for help, it is because their junior or senior has passed some of the EOCs, but still lacks having all five needed for graduation. And time is running out.

The good news is that for many of these kids, they do not need to pass all five EOCs to graduate. For most of them, the IGC (Individual Graduation Committee) option offers them a path to the diploma. A diploma issued by the IGC is precisely the same as the diploma a student who passes all five EOCs will receive. There is no notation or limitation on the student’s ability to attend college, enter the military, or make any other use of their high school diploma as a result of using the IGC process.

Who is Eligible to Graduate Via IGC?

This is determined by the plain language of the statute: “This section applies only to an 11th or 12th grade student who has failed to comply with the end-of-course assessment instrument performance requirements under Section 39.025 for not more than two courses.” Tex Educ. Code §28.0258 (a). Now this seems simple enough – pass three out of five and you are eligible — but there are a few caveats to deal with.

First, the Commissioner has added requirements to the statute. We can argue about whether he can restrict access to IGC graduation in a manner that the legislature did not, but for purposes of this article we are trying to get you to the IGC without a fight. The commissioners rules add an “attempt” requirement to IGC eligibility.

A student may not graduate under an individual graduation committee if the student did not take each EOC assessment required by this subchapter or an approved substitute assessment in Subchapter DD of this chapter (relating to Commissioner’s Rules Concerning Substitute Assessments for Graduation) for each course in which the student was enrolled in a Texas public school for which there is an EOC assessment. A school district or charter school shall determine whether the student took each required EOC assessment or an approved substitute assessment required by Subchapter DD of this chapter. For purposes of this section only, a student who does not make an attempt to take all required EOC assessments may not qualify to graduate by means of an individual graduation committee.

19 TAC §101.3022(e). Here the commissioner rules say two different things while repeating itself. First, it says that to graduate by IGC, the student must have actually taken each EOC or a substitute assessment for each course they took in a Texas public school that has an EOC attached to it. Then at the end, it seems to say that they must actually have attempted all of the EOCs, not the EOC or substitute assessment. Let me be clear that I do not think this intends to say that a student who passes a substitute assessment and never attempts the EOC cannot graduate by IGC. Or similarly, if the student took and passed Algebra I in Oklahoma (and thus exempt from EOC passage), I don’t think this rule means he has to attempt the Algebra I EOC before being eligible to graduate by IGC. But I do think that if they fail to pass the substitute assessment and never attempt to the EOC for that course, the school might deny them access to the IGC. For that reason, if you are relying in an IGC to graduate, we recommend that you attempt each EOC that you are missing one time. Refusing in person (turning in a blank answer sheet or tabbing through to the endand submitting) is an attempt.

How do we count “no more than two.”

As a matter of shorthand, we often say things like “3 out of 5” makes you eligible for an IGC. But we really do need to use the no more than two language. The number of required assessments to graduate is going to vary according to the student. As sec. 29.025 points out, the satisfactory performance requirement only applies to “a course in which the student is enrolled and for which an end-of-course assessment instrument is administered.” If the student was in private school or out of state at the time of their enrollment, they do not have to pass an EOC to graduate. So those do not count when counting whether the student “has failed to comply with the end-of-course assessment instrument performance requirements under Section 39.025 for not more than two courses.”

Example 1: Joe takes and passes Algebra I and English I in private school in 9th grade. In 10th grade, he goes to public school, takes and passes the Biology I course and EOC, passes English 2 course but fails the EOC, and then passes US History in 11th grade, but fails that EOC also. Joe is eligible to graduate by IGC. Sec. 39.025 only required that he take and pass Biology, English II and US History to graduate. Even though he has only passed one EOC, he has failed to comply with the requirement in only two classes. Because he has not failed to comply in more than two classes, he remains eligible to graduate under an IGC.

Example 2: Miranda is a newly arrived ELL student in 9th grade. She received the ELL exemption from passing English I and the assessment is not administered to her. She fails all her 9th grade EOCs that she attempts, but later passes Algebra I and Biology. She fails passes all her classes, but fails her English 2 EOC and her US History EOC. Miranda is not eligible to graduate by IGC. Although she has only failed two EOCs, her exemption from English I comes from an administrative rule, and not from sec. 39.025. She has failed to comply with sec. 39.025 requirements in English I, English 2 and US History. This is more than two classes. Note that if Miranda passed all EOCs other than the English I exempted EOC, she would not need an IGC because she could graduate using her exemption.

When does the IGC meet?

This is one of the most frustrating parts of the statute. The law provides that the school “shall establish an individual graduation committee at the end of or after the student’s 11th grade year to determine whether the student may qualify to graduate as provided by this section.” Unfortunately, the day before 12th grade graduation is still “after” the 11th grade year, and many schools have taken this approach of waiting to the last minute. The good news? The law expressly permits schools to start the IGC process as soon as 11th grade ends. There is no need to sweat graduation to the last minute. Parents should request the IGC be established at the end of 11th grade and be persistent in the Fall of 12th grade. The IGC can meet, prescribe any remediation required, and ease everyone’s concerns as the student completes any required work. If the school claims they do not meet until late spring, remember this is not a legal requirement. Rather it is just a local preference. There is no reason the school cannot get started in the fall. You should be persistent with the campus and district administration seeking an early start to the process. Engage your local school board if needed. Keeping people hanging on and worried is unnecessary, counterproductive and often just punitive. We should not tolerate it. In all things, document in writing and record phone calls.

Do I have to keep taking the EOCs every time they come up?

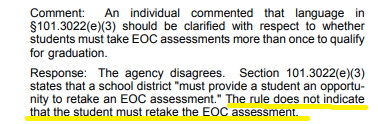

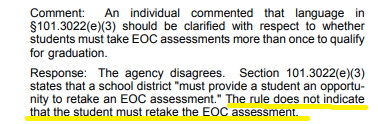

NO! Even the commissioner’s rules only require a single attempt. The school is required to offer it. Your choice not to take it does not disqualify you from IGC eligibility. When the IGC process was new, a very uninformed ESC put out a powerpoint claiming there was a two attempt requirement for IGC eligibility. It spread like wildfire because there was no other guidance available. We had to intervene to get this corrected at the ESC level, but many campuses still believe it. Even in the last two years, Pearland ISD has claimed a two attempt requirement existed. It doesn’t. We even wrote an article about it. IGC Graduation Does NOT Require Two Failed Attempts on EOCs The myth was so pervasive that the TEA even had to respond to it in its rulemaking,

99 Tex Reg 5900, 5901 (Oct. 11, 2019). One attempt satisfies the commissioner’s rule. Nothing else is required.

99 Tex Reg 5900, 5901 (Oct. 11, 2019). One attempt satisfies the commissioner’s rule. Nothing else is required.

Who is a member of the IGC?

The commissioner rules (19 TAC 74.1025) answer this question. The individual graduation committee shall consist of the following:

(1) the principal or principal’s designee;

(2) for each EOC assessment instrument on which the student failed to perform satisfactorily, the teacher of the course;

(3) the department chair or lead teacher supervising the teacher described by paragraph (2) of this subsection; and

(4) as applicable:

(A) the student’s parent or person standing in parental relation to the student;

(B) a designated advocate if the person described by subparagraph (A) of this paragraph is unable to serve; or

(C) the student, at the student’s option, if the student is at least 18 years of age or is an emancipated minor.

In the event that the teacher identified in subsection (f)(2) of this section is unavailable, the principal shall designate as an alternate member of the committee a teacher certified in the subject of the EOC assessment on which the student failed to perform satisfactorily and who is most familiar with the student’s performance in that subject area.

In the event that the individual identified in subsection (f)(3) of this section is unavailable, the principal shall designate as an alternate member of the committee an experienced teacher certified in the subject of the EOC assessment on which the student failed to perform satisfactorily and who is familiar with the content of and instructional practices for the applicable course.

A few practical notes: schools often try to stack these committees with all sorts of people that are not on the list above: counselors, testing coordinators, multiple administrators. So long as the outlook is “how do we get this kid graduated” that shouldn’t be a problem. However, if it starts to get contentious, realize that there may be people piping up who shouldn’t even be in the room. It may make sense to identify who is actually on the committee and ask those who are not to either leave, or not interrupt the discussions.

With students who are 18, the parent is the presumed representative. However, because the student has the option to serve instead, schools often pull students from class and try to do these meetings on little to no notice. This is one reason to be proactive in getting the meetings scheduled. Also, discuss the importance of the meeting with your kid and see if he will write a directive to the school that they want you representing them and should contact you for any meetings.

How does the IGC make its decision?

To understand the various factors the legislature requires the committee to review, it is helpful to look at the IGC meeting guide from ESC 12. (View the form here.)

In Section III you will find the required committee considerations. No single factor has dispositive weight. It is not the case that one “no” on a factor means you can’t graduate. Rather the test is a balancing test and the committee can use its discretion to weight each factor as it sees fit. At the end of the day, the committee can make a recommendation to graduate the student or not. If the decision is to graduate them, they must require either a project in each lacking EOC course or the preparation and review of a portfolio demonstrating mastery of the subject. We strongly urge parents to retain work from each EOC course that is not passed so the portfolio is a viable option. Save good test results, papers that got good grades and any other work that shows the student has a mastery of the subject. Without this, it is impossible to do a portfolio and you must default to a project, which means new work.

What can the IGC require for graduation?

A project or a portfolio for each course that does not have a passing EOC or substitute assessment must be assigned if the student is permitted to graduate. The committee is also permitted to assign additional remediation in the subject areas. This is another reason to demand an early IGC meeting. If there is going to be remediation, the student should know about it well before graduation.

My schools says a project is required for the IGC, is this true?

No, there is no specified project requirement. In theory, the IGC makes an individual determination for each student. A project is one potential requirement.

How many votes do I need to graduate?

The decision of the committee must be unanimous. This is why it is important that only the actual members participate and vote, and that anyone with a conflict of interest not participate.

Can I appeal a determination that denies graduation?

No, the decision of the committee is final.

Recommendations for Parents

- Try to use substitute assessments to graduate/gain eligibility for IGC. If your student has successfully completed the substitute assessment requirements, they do not need an EOC result to graduate. For students who approach senior year lacking assessments, ask whether the student has taken PSAT, SAT or ACT. Many schools give PSATs to 9th graders. Those results are in their file and may meet Algebra I or English I standards. If the sub assessment score is good enough, you don’t need the EOC and might pick up the missing assessment you need to graduate or get to committee.

- Save all work from EOC courses. Preserve the portfolio option! Set aside tests, worksheets, projects and papers from each EOC course until you know if they have passed the EOC of substitute assessment.

- Start the IGC process early. Do not wait for the school to contact you! As soon as 12th grade starts, get that IGC issue in front of the school and get a meeting set.